Three years ago I wrote a post about watching local content on Amazon’s Fire TV via Plex. At that time, we watched content via Mac minis connected to LED TVs. The main problem with this approach was the accessibility to online services such as Amazon Prime Video and Netflix. You had to wrangle a keyboard and mouse from the couch, and that was just cumbersome (and not kid-friendly).

I expressed my desire in that post for Amazon to release a stick version of their Fire TV, similar to Roku’s Streaming Stick. I had tried out Roku’s stick, and didn’t like it much. Well, they did eventually release a Fire TV Stick, but I opted to purchase the full boxes instead.

Since that post, we have converted to watching content via Fire TVs connected to those same LED TVs. We still have those Mac minis connected (although they mainly serve their purpose as Plex Media Servers and OTA DVRs). These Fire TV boxes are great, and fairly stable. We mainly watch Plex content on them, but they are also an easy way to consume Amazon’s video and music library, while also providing easy access to YouTube (a service I thoroughly enjoy watching vlogs [and the occasional fail compilation] on).

Since purchasing those Fire TVs, we delve even deeper into the Amazon ecosystem and purchased Fire tablets for the boys. I was hesitant to adopt the Android platform (being so firmly in the iOS camp), but it works great for the boys (who also have their own iOS devices to keep them grounded in truth). Don’t get me wrong, I will always be loyal to iOS, and I would never buy an Android phone. But for cheap tablets, these things are great.

This has been today’s Clarified Butter.

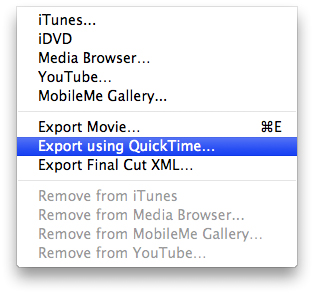

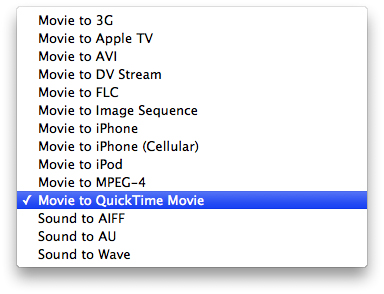

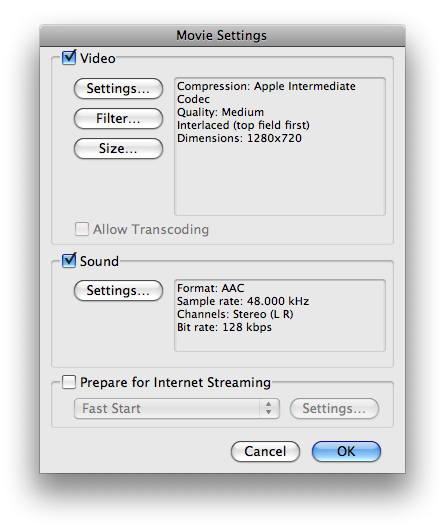

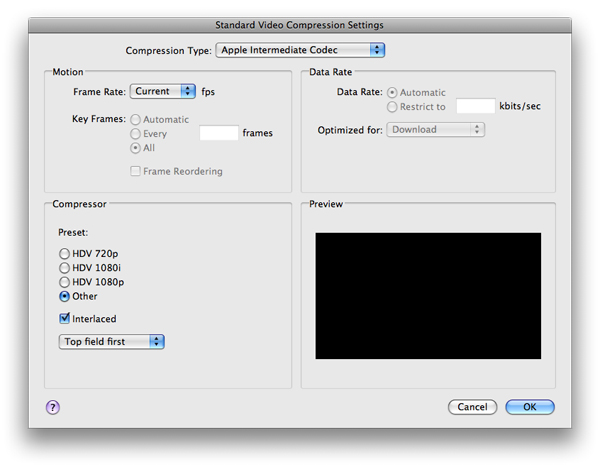

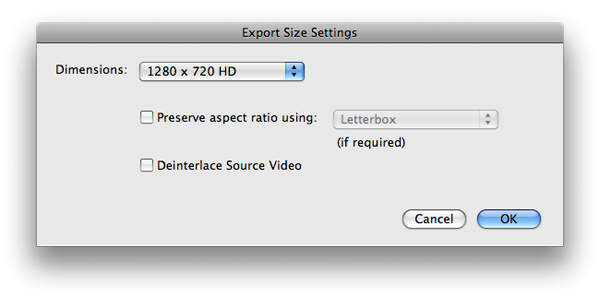

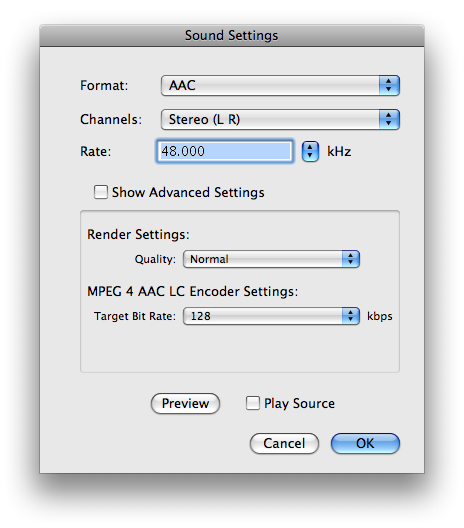

So, assuming that you’ll be using the newest version of iMovie and iDVD, the method of importing and editing your video remains the same. The quality retention (at least the best it can be), is handled when the video is complete, and being exported to iDVD. You’d think that using the Share > iDVD menu item would give you the best possible quality. This isn’t so. The trick is using Share > Export using QuickTime…

So, assuming that you’ll be using the newest version of iMovie and iDVD, the method of importing and editing your video remains the same. The quality retention (at least the best it can be), is handled when the video is complete, and being exported to iDVD. You’d think that using the Share > iDVD menu item would give you the best possible quality. This isn’t so. The trick is using Share > Export using QuickTime…

I think we have a unique situation here at ProGravix. Seeing as how we are graphic designers and web developers, we have an advantage over other videographers that don’t share this same skill set. First, and foremost, we are graphic designers. This bleeds over into web development. But how can it help with videos we create? Tons. Certainly the actual capture, editing, and display of that video is a substantial part of the project. But I think making an impact with the packaging is extremely important. As graphic designers, we use our expertise to create engaging, studio quality DVD cases and faces that invite the viewer in, and give an impression that what they are about to watch is an important keepsake.

I think we have a unique situation here at ProGravix. Seeing as how we are graphic designers and web developers, we have an advantage over other videographers that don’t share this same skill set. First, and foremost, we are graphic designers. This bleeds over into web development. But how can it help with videos we create? Tons. Certainly the actual capture, editing, and display of that video is a substantial part of the project. But I think making an impact with the packaging is extremely important. As graphic designers, we use our expertise to create engaging, studio quality DVD cases and faces that invite the viewer in, and give an impression that what they are about to watch is an important keepsake.