One of the most difficult obstacles to overcome is getting your client to trust your artistic and creative judgement. After all, they are coming to us for a specific reason: They have little (or don’t trust) personal creativeness. Knowing that a very high percentage of our clients made their way to ProGravix via Word of Mouth™, this usually can be overcome with very little persuasion.

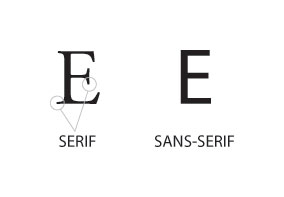

As an example, many clients prefer to specify specific design elements that they prefer, namely fonts. I’ve had several clients expressly request that I use a font such as Arial or Calibri for chunks of text. They see a font, and think it looks clean or neat, and wish to use it throughout. The problem is that these fonts, known as sans-serif fonts, are difficult to read when used in large groups of words (such as paragraphed text). The solution is to use a serif font. But what’s the difference?

Serif fonts are those that have the little stylized ‘feet’ at their base and throughout the corners and ending points of the character. Sans-serif fonts are great for headlines, callouts, and other minimum word areas. And when used sparingly, all caps is appropriate. An example of this would be headlines in a newspaper. Alternatively, all caps serif fonts tend to be difficult to read. Look at nearly all standardized road signs. They all use Helvetica, all caps. Yes, I am sure some municipalities stray from this international standard, attempting to present their roadways and byways in a rustic or colonial fashion, but overall ‘caps sans’ is where road signs are at.

And although this does not really follow the same topic, there is another piece of advice I’d like to share: There is only 1 space after a period (or any other sentence ending punctuation mark). Now just stay with me here… Back when I first learned to type, it was on an IBM manual typewriter. And at that time, the rule was to place two spaces after a period. But why? Well, in those manual typewriter days, the font used was always monospace, such as Courier. Monospace means that all characters, punctuation, et cetera, used the same exact width. So, two lower case L’s would appear very far apart, while two capital W’s, would appear squished together. So, the thinking was that those two spaces after a period would visually present a new sentence, and in theory allow you to more easily read the text. Nowadays, with computers, we should only be using a single space after periods. See, the computer is smart enough to know what spacing should be implemented along with that period and single space, based on the font in use. Yes, if you MUST use a monospace font (and they are certainly around), still use the double-space method. Not because the computer is suddenly space-period-dumb, but because this is obviously the look you are going for: horribly stylized ransom note.

This has been today’s Clarified Butter.